Italian Journal of Quaternary Sciences

10(2), 1997, 529-534

Genesis of isolated synclines: is gravitational stress sufficent to create them?

A. Borgia 1, S. Carena1, A. Battaglia2, G. Pasquare' 2, A. Tibaldi2, M.T. De Nardo3, L. Martelli3.

1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica, Roma.

2 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita' degli Studi di Milano.

3 Regione Emilia-Romagna, Ufficio Geologico, Bologna.

Riassunto

Nell'Appennino Settentrionale si trovano alcune brachisinclinali costituite da rocce calcaree o arenacee poggianti su materiali argillosi. Quasi del tutto assenti le anticlinali, talvolta sono presenti alti morfo-strutturali. La genesi di queste strutture è in genere attribuita alle principali fasi tettoniche dell'Appennino (Miocene superiore e Pliocene inferiore). Il nostro lavoro indica, come ipotesi alternativa, che la tettonica gravitativa potrebbe avere giocato un ruolo importante nella loro formazione, accentuando anche alcune caratteristiche morfologiche sinsedimentarie. Una di queste strutture, la sinclinale di Vetto-Carpineti, è un'estesa placca la cui base è costituita da mélanges argillosi e dalle Marne di Monte Piano su cui poggiano, nell'ordine, le formazioni di Ranzano, Antognola e Bismantova. Il substrato della placca è prevalentemente formato da unità argillose e con assetto caotico (mélange di Pietra Nera, argilliti di Lupazzano, Argille Varicolori s.l., "Argille Ofiolitifere" Auctt., Argille a Palombini). I versanti esterni della struttura hanno una morfologia molto più acclive di quelli interni, e invariabilmente presentano strati disposti a reggipoggio. Il nucleo della sinclinale non contiene riempimento sedimentario post-tettonico, fatta eccezione per una sottile coltre di depositi eluvio-colluviali. La placca è tagliata in direzione N-S dal Torrente Enza, che attualmente scorre in meandri incassati circa 300 m più in basso rispetto al fondo del bacino formato dalla brachisinclinale. Il grado di deformazione delle rocce è ridotto in corrispondenza della sinclinale, raggiunge il massimo livello nei complessi caotici soggiacenti ed adiacenti e torna a diminuire a distanza maggiore. Nella zona di massima deformazione le unità argillose si trovano circa alla stessa quota del fondo della sinclinale. Faglie e sovrascorrimenti alla base della placca hanno direzioni parallele ai suoi margini. Il nostro lavoro suggerisce che la sinclinale di Vetto-Carpineti potrebbe avere avuto una genesi in quattro stadi parzialmente sovrapposti: (1) emersione dal mare, (2) erosione dei litotipi meno resistenti circostanti la placca arenacea, (3) piegamento gravitativo della placca ed estrusione laterale dei complessi argillosi sottostanti, (4) sollevamento. Le ultime fasi dellíevoluzione su esposta sono probabilmente di etàmedio e tardo-pleistocenica.

1 Introduction

The role of gravity in orogenesis had already been stressed by several authors at the end of the 19th century (Bombicci, 1882; Reyer, 1892) and at beginning of this century (Ampferer, 1934; de Wijkerslooth, 1934; Lugeon, 1940), as underlined by Dal Piaz (1941).

Since 1960 numerous studies describe the deep-seated gravitational deformations in slopes (see for example Beck, 1968; Ter-Stepanian, 1977; Radbruch-Hall et al., 1977; Forcella, 1984; Varnes et al., 1989; Dramis & Sorriso-Valvo, 1994). These studies focused on various aspects of a much broader issue, that is the role of gravity in crustal deformation.

We study the role of gravity in the formation of isolated synclines that form when a plate of brittle rock rests on a ductile substratum. We first describe the geology, then we present analytical, numerical, and analogue modeling to obtain a general solution for this geologic problem, that is complementary to that of diapirism. We chose the Northern Apennines, an area where there are several instances of isolated synclines. Up to now the genesis of these structures was referred to compression during the main tectonic phases of the formation of the Apennines. Our work instead indicates that gravitational tectonics could be responsible for their formation.

This result casts a new light on the structural interpretation of the late stages of formation of the Apennines and other areas with similar structures.

2 Geological setting

The Northern Apennines, Italy, are part of the collisional margin between the African and the European plate. During their formation the tectonic transport was toward the NE (Papani et al. 1987). Within this chain there are a number of piggy-back sedimentary basins (Middle Eocene-Serravillian in age), of which the Epiligurian Vetto-Carpineti-Canossa basin (VCC) is nested on the Ligurian thrust sheets.

The studied area is formed by three sub-basins within the principal VCC basin, 30 km south of the town of Parma. The sub-basins are the Scurano-Vetto-Carpineti, the Ranzano-Sasso, and the Groppo-Tassobbio. The VCC basin lies unconformably on a basement formed by a number of units varying in age and rheological behavior.

The stratigraphy of the area consists of highly tectonized Ligurian

Units formed during the emplacement of the Ligurian thrust (Late

Creatceous-Middle

Eocene tectonic phase), unconformably overlain by olistostromes and

then

by younger and less deformed pelitic and arenaceous turbiditic units

belonging

to the Epiligurian sequence (De Nardo et al., 1990). Between these two

sequences there are other units formed by chaotic clayey materials,

characterized

by pervasive multi-phase deformation, that can enclose tectonized

blocks

up to a few hundred metres in dimension, of ophiolites, limestones, and

sandstones. Vai & Castellarin (1992) interpreted them as complexes

originated during the Eo-alpine phase, whereas Papani et al. (1987)

interpret

at least some of them as Tertiary mélanges of reworked Ligurian

material, formed in the interval Early Eocene-Aquitanian.

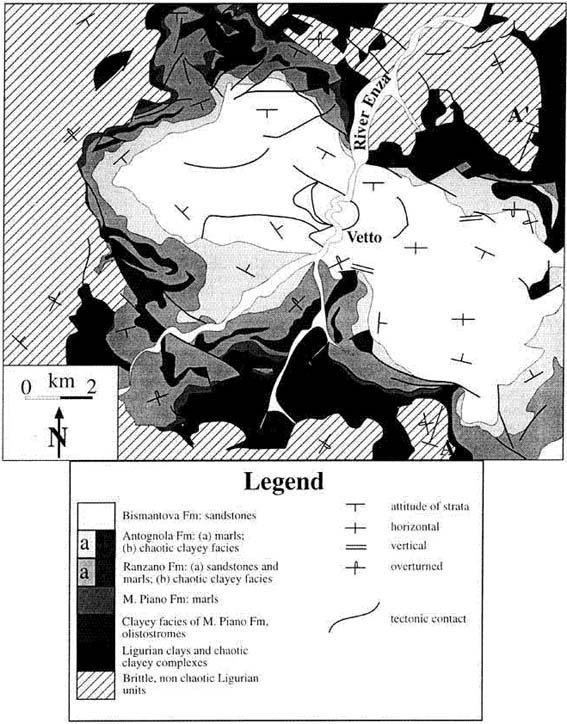

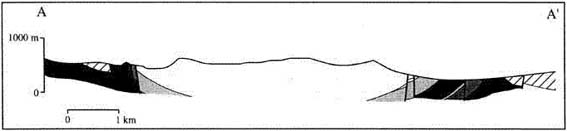

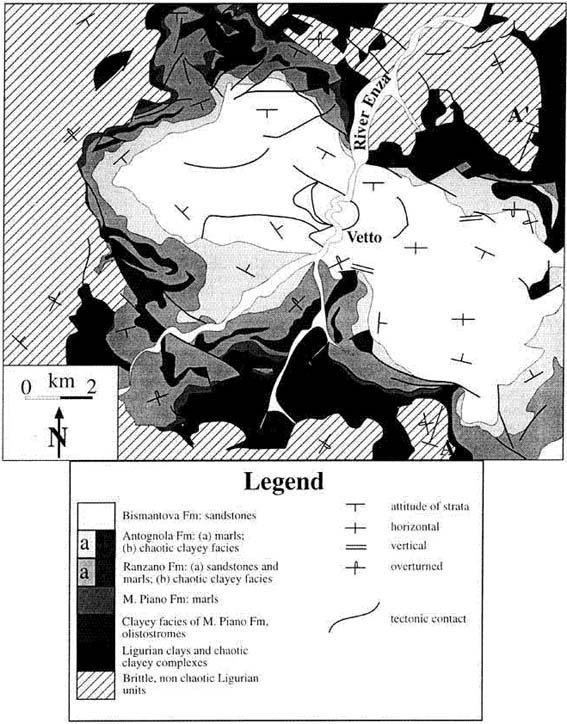

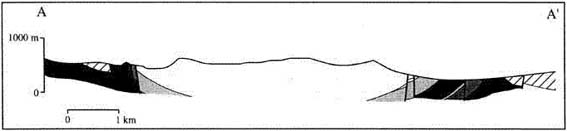

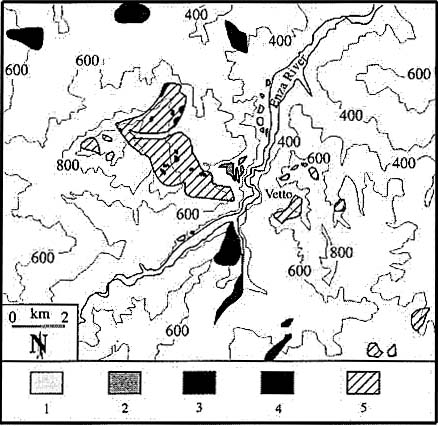

Fig. 1 - (Above) Schematic geo-rheological map. Dashed areas show the brittle substratum; grayscale indicates the rheology of rock units from "brittle" (light) to "ductile" (dark). Data are from the 1:10,000 Geologic Map of Emilia-Romagna, and this work. (Below) Cross-section showing a clay diapir at the southern end of the plate (same legend as above).

(Sopra) Carta geo-reologica schematica. Il retinato diagonale e' il basamento "fragile"; la scala di colori grigi indica la reologia delle unita' da "fragile" (chiaro) a "duttile" (scuro). Dati derivati dalla Carta Geologica dell'Emilia-Rimagna alla scala 1:10:000 e da questo lavoro. (Sotto) Sezione geologica. Un diapiro di argilla e' visibile all'estremita' meridionale della placca (stessa legenda della parte alta della figura).

3 Geology and geomorphology

3.1 Geomorphologic data

The Epiligurian turbiditic sandstones form a brachisyncline (the Vetto-Carpineti syncline, Papani et al. 1987) overlying the clayey basement. The syncline forms a bowl-shaped mesa-like relief (plate) that stands out on the surrounding clay-rich, more erodible rocks. The bowlís bottom is at about the same elevation of the clayey materials outside and around the plate. The maximum elevation corresponds to the western end of the plate. The bowl is deeply dissected in two parts by the Enza river in a NNE direction. The western half of the plate is well preserved, with little erosion and a rather continuous perimetral cliff, while the eastern part is much more eroded and presents deep valleys which interrupt the cliff.

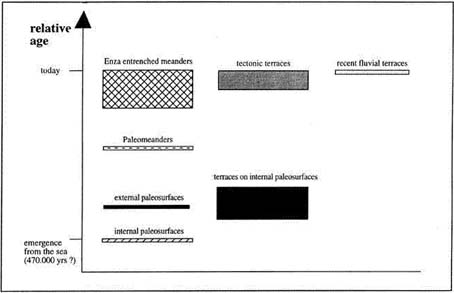

The field survey showed a number of paleosurfaces that cut each other in a time sequence from older to younger, as represented in figure 1.

An erosional paleosurface (internal paleosurface) occupies nearly half of the western part and is parallel to the strata. In the eastern half there are only a couple of small remnants of a similar surface. These surfaces may be the remnants of the old marine abrasion plane.

Other paleosurfaces (external paleosurfaces), that cut the strata, are found around the plate, like for example a buried terrace on the lower hills around the "mesa".

Paleomeanders and terraces can be recognized inside the "bowl". Terraces dipping toward the center of the bowl are found at various elevations on the internal paleosurface; their position and distribution indicates a lacustrine origin for at least some of them. In the west, paleomeanders are entrenched into the Bismantova Formation (see figure 2b). The present meanders of the Enza river are also entrenched in the Bismantova Fm., for a minimum of 300 metres in the central part of the plate.

Along the river banks a number of recent terraces can be found: some are cut into the Bismantova Fm, others into ephemeral alluvial and lacustrine deposits of the Enza river itself. There are also several tectonic terraces due to block tilting caused by normal faults along the Enza river.

3.2 Lithologies and stratigraphic relationships

The lithologies involved and their stratigraphic relationships are shown in figure 2a and 2b.

The oldest lithologies encountered in the area belong to the Ligurian Units and form the plate basement that contains a variety of clays and clayey chaotic units whose origin and age are seldom defined, but which have similar rheological properties. These complexes have variable thickness (from about 100m to 1000m): the maximum is in the area east of the Enza river, while at the western end of the plate the thickness is minimal.

The principal of these units is the ëArgille Varicolori Fm.í, formed by multicoloured banded clayey shales showing a characteristic isoclinal and complex folding.

The Ligurian basement contains also a number of brittle units, particularly slabs of flysch formations present in the western zone.

Above the basement there are the Epiligurian Units, that begin with a ductile level made of olistostromes, mélanges, and clayey units of the M.Piano Fm., with a thickness of about 100 m and a rheology comparable to the deformable units in the basement (for this reason, when using the term "substratum", we will refer to all the ductile deformable units below the plate, including the Epiligurian olistostromes and clays.) On top there is the brittle level corresponding to the plate, formed by the sequence M. Piano- Ranzano-Antognola-Bismantova Fms, a mainly turbiditic sequence where sandstones predominate in the upper part and marls predominate in the lower one. Deformable chaotic lenses are embedded in the Ranzano and Antognola Formations, like the "Canossa Olistostrome" (Papani, 1971) in the Antognola Formation. The plate sequence thickness can vary from several hundred metres in the west to more than a thousand metres in the east.

The Bismantova Fm, Langian to Serravillian in age, is the youngest one; the nucleus of the syncline doesn't contain any sediments apart from a veneer of alluvial and colluvial deposits.

3.3 Structural data

3.3.1 Deformations in the arenaceous plate

The plate is bent into a brachisyncline elongated in a E-W direction, reflecting the original shape of the sedimentary basin. Strata always dip inward on the outer cliffs of the "mesa", and are parallel to the topographic surface of the "bowl".

Along the plate margin there are large normal faults with arcuate fault trace (fig. 2b), they cause hanging walls to slid away from the center of the plate. These faults are very clear in aerial photographs, but have poor evidence in the field because of the relatively small erosion. Active normal faults form a collapse structure toward the Enza river. Their activity is documented by the well-defined fault scarps and open fractures that move periodically.

The Antognola Formation presents several large asymmetric folds, that involve the underlying Ranzano Formation; they show both apenninic and alpine trends, and seem to have formed when still in the sedimentary basin.

3.3.2 Deformations in the surrounding chaotic units

The most relevant structures are: 1) the isoclinal folding evident in several types of banded clayey shales; and 2) the chaoticization of some clays and of clayey formations.

In the substratum there are several small thrusts and strike-slip faults that parallel the plate margins. Thrusts vergence is almost invariably away from or towards the plate.

Three clay diapiric structures (figure 2b) occur, one at the easternmost plate edge, the other two along the southern margin of the "mesa" (one is visible in the cross section of figure 2a). The contact between plate and clay diapirs is delaminated and sandstone strata around them are vertical to overturned. These diapirs form elongated "tongues" of substratum into the plate. Pieces of M. Piano-Ranzano sequence, stretched and overturned, are found sourrounded by the clays along the north-eastern margin of the plate. The deformation and density of structures in the clays are high in proximity of the contact with the plate, they diminish toward and away from it.

Fig. 2 - (Above) Morphological map indicating the major paleosurfaces (from youngest to oldest): 1) recent alluvial deposits; 2) slump-related terraces; 3) terraces on internal paleosurface; 4) external paleosurface; 5) internal paleosurface. Map based on 1:5000 scale maps (Carta Tecnica Regionale, Regione Emilia-Romagna), 1:15,000 stereo-aerial photographs and uor field work; elevations are in meters a.s.l. (Below) Relative age distribution af morphological features; see text for discussion on the estimate age of emergence from the sea.

(Sopra) Carta morfologica delle principali paleosuperfici (dalla piu' giovane alla piu' vecchia): 1) depositi alluvionali recenta; 2) terrazze legate a "slumps"; 3) terrazze sulle paleo superfici interne; 4) paleosuperfici esterne; 5) paleosuperfici interne. Carta basata sul rilievo 1:5.000 (Carta Tecnica Regionale, Regione Emilia-Romagna), le foto aeree stereoscopiche 1:15.000 ed il nostro rilievo di campagna; quote in metri s.l.m. (Sotto) Eta' relative degli elementi geomorfologici; vedere il testo riguardo all'eta' stimata per l'emersione.

4 Discussion and conclusions

The fact that the bowlís bottom (the nucleus of the syncline) is at the same elevation of the substratum outside the plate demonstrates the sinking of the plate central zone into the clayey units, with consequent lateral squeezing and bulging of the underlying clays. In this context clays are also squeezed upward through faults and fractures to form diapirs.

The thickness of clays is a fundamental parameter conditioning the velocity and extent of plate sinking: at the western end, minimum thickness of clays corresponds to maximum elevation of plate (minimum sinking) and least deformation, while at the eastern end, maximum thickness of clays is associated with lesser elevations and maximum structural complexity.

This is the hypothetical evolution of the area:

- At sea level the first erosional surface formed.

- The onset of deformation should correspond to the emergence from the sea because, to allow sinking of the plate into the clays, the plate must have been at least partially isolated by erosion. During deformation, a lake formed inside the growing syncline; marine erosional surfaces formed outside the plate.

- With further regional uplift and deformation, the northern barrier of the lake was eroded, the lake disappeared, and paleomeanders formed inside the syncline; meanwhile, the external paleosurfaces were bent toward the syncline.

- While the uplift continued, the Enza river formed the present entrenched meanders and caused the formation of several tectonic terraces along its banks. Finally the present alluvial terraces formed.

The well preserved western paleosurface suggests a Quaternary age ( Amorosi et al., 1996). Quaternary continental deposits immediately north of this area of the Apennines are <800.000 years old, with a stratigraphic and angular unconformity at 470.000 years. Therefore this last event probably dates the regional uplift (Di Dio et al., 1996) that is related to the bending of the plate.

A Quaternary gravitational bending of the plate, well after the end of the great regional tectonic phases, can also explain why faults and thrusts do not follow the regional trend, but instead they parallel the plate margins.

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Moratti and two anonymous reviewers for helpful criticism. Financial support for this work was provided by ING, GNV-CNR grant n. 97.00109.FP62 and Regione Emilia-Romagna.

References

Ampferer O. (1934) - Ueber die Gleitformung der Glarner Alpen. Sitzungsber Akad. Wissen. Wien, Math.-naturw. Kl. Abt. I, 143 Bd, 109-121.

Beck A.C. (1968) - Gravity faulting as a mechanism of topographic adjustment. N.Z. Journ. Geol. Geophys., 11, 191-199.

Bettelli, G., and F. Panini (1987) - I melanges dell'Appennino Settentrionale dal T. Tresinaro al T. Sillaro. Mem. Soc. Geol. It., 39, 187-214.

Bombicci L. (1882) - Il sollevamento dellíAppennino bolognese per diretta azione della gravità e delle pressioni laterali, con appendice sulle origini e sui reiterati trabocchi delle argille scagliose. Mem. Accad. Sc. Ist. di Bologna, Serie IV, Tomo III, pag. 641.

Dal Piaz, G.(1942) - L'influenza della gravità nei fenomeni orogenetici. Atti Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino, vol. 77 e 78, 1-51.

De Nardo, M.T., S. Iaccarino, L. Martelli, C. Tellini, L. Torelli, and L. Vernia (1991) - Osservazioni sull'evoluzione del bacino satellite epiligure Vetto-Carpineti-Canossa (Appennino Settentrionale). Mem. descrittive della carta geologica d'Italia, XLVI, 209-220.

de Wijkerslooth P. (1934) - Bau und Entwicklung des Apennins besonders der Gebirge Toscanas. Selbstverlag. Geologisch Instituut-N. Prinsengracht 130, Amsterdam, I-XII & 1-424.

Di Dio G., S. Lasagna, D. Preti, M. Sagne (1996) - Carta Geologica dei depositi quaternari della Provincia di Parma.

Dramis, F., & M. Sorriso-Valvo (1994) - Deep-seated gravitational slope deformations, related landslides and tectonics. Engineering Geology 38, 231-243.

Forcella F. (1984) - The Sackung between Mount Padrio and Mount Varadega, Central Alps, Italy: a remarkable example of slope gravitational tectonics. Méditerranée 1.2 (1984), 81-92.

Lugeon M. (1940) -Sur la formation des Alpes franco-suisses. C.R. somm. Soc. Géol. France, 7-10.

Papani G. (1971) - La geologia della struttura di Viano (Reggio Emilia). Mem. Soc. Geol. It., 10 (2), 121-165.

Papani G., C. Tellini, L. Torelli, L. Vernia, and S. Iaccarino (1987) - Nuovi dati stratigrafici e strutturali sulla Formazione di Bismantova nella "sinclinale" Vetto-Carpineti (Appennino Reggiano-Parmense). Mem. Soc. Geol. It., 39, 245-275.

Radbruch-Hall D.H., D.J. Varnes, R.B. Colton (1977) - Gravitational spreading of steep-sided ridges ("sackung") in Colorado. Jour. Res. U.S. Geol. Survey, 5, 359-363.

Reyer Ed. (1892) - Cause delle dislocazioni e della formazione delle montagne. (trad. it. di F. Virgilio, Torino, Vincenzo Bona.

Ter-Stepanian G.I. (1977) - Deep-reaching gravitational deformation of mountain slopes. Bull. Int. Ass. Eng. Geol. 16, 87-94.

Vai G.B. and A. Castellarin (1992) - Correlazione sinottica delle unità stratigrafiche dell'Appennino Settentrionale. Studi Geologici Camerti, vol. speciale (1992/2), CROP 1-1A, 171-185.